Can a Woman With Mental Illness Have a Baby

- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

Pre-existing mental wellness disorders bear on pregnancy and neonatal outcomes: a retrospective cohort report

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth volume 20, Article number:419 (2020) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

This was a infirmary registry-based retrospective historic period-matched cohort written report that aimed to compare pregnancy and neonatal outcomes of women with pre-existing mental disorders with those of mentally healthy women.

Methods

A matched accomplice retrospective written report was carried out in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Hospital of Lithuanian University of Wellness Sciences Kauno Klinikos, a tertiary health care institution. Medical records of pregnant women who gave nascence from 2006 to 2015 were used. The study grouping was comprised of 131 pregnant women with mental disorders matched to 228 mentally salubrious controls. The primary outcomes assessed were antenatal care characteristics; secondary outcomes were neonatal complications.

Results

Pregnant women with pre-existing mental health disorders were significantly more likely to take low education, be unmarried and unemployed, have a disability that led to lower working capacity, smoke more frequently, have chronic concomitant diseases, attend fewer antenatal visits, proceeds less weight, exist hospitalized during pregnancy, spend more time in infirmary during the postpartum period, and were less likely to breastfeed their newborns. The newborns of women with pre-existing mental disorders were small-scale for gestational historic period (SGA) more often than those of healthy controls (12.9% vs. seven.half dozen%, p < 0.05). No deviation was plant comparison the methods of delivery.

Conclusions

Women with pre-existing mental health disorders had a worse course of pregnancy. Mental illness increased the risk to evangelize a SGA newborn (RR 2.055, 95% CI 1.081–3.908).

Groundwork

Mental disorders are among the well-nigh mutual conditions affecting women of reproductive historic period. The World Health Organization recognizes that 10%−16% of pregnant women and 13%−twenty% of postpartum women worldwide experience mental disorders, and virtually of these women suffer from depression [1].

Untreated perinatal mental disorders have a meaning negative impact on both maternal and fetal health [2]. Because of the changes in women'south neurochemistry acquired past identical peptides and proteins synthesized by the encephalon and the placenta during pregnancy (brain-derived neurotrophic factor, oxytocin, vascular endothelial growth factor, cortisol, matrix metalloproteinase), women with untreated mental disorders (anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia, depressive disorders) are at an increased risk of obstetric complications such as preterm birth and delivery of depression-birth-weight and pocket-size-for-gestational-age (SGA) newborns [3]. In addition, in that location are multiple other factors that increase the probability for agin delivery outcomes, including genetic predisposition, maternal stress, sociodemographic disadvantage, poor nutrition, addiction to psychoactive substances, and poor antenatal care (ANC) omnipresence [4,5,6].

Other studies suggest that women with mental disease accept a higher rate of overall complications in their pregnancy. All the same, the findings on the take a chance to deliver SGA newborns are not consistent [7,8,9,10,xi,12].

The aim of our written report was to clarify sociodemographic, pregnancy and delivery outcomes of women with pre-existing mental disorders and to compare them with the outcomes of mentally salubrious women as well as to determine whether women with pre-existing mental disorders had worse perinatal outcomes.

Methods

A infirmary registry-based retrospective matched cohort written report, involving women with pre-existing mental disorders that gave birth in the Section of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Lithuanian University of Health Sciences Kauno Klinikos, from January 1, 2006, to December 31, 2015, was carried out. The study was approved by the Lithuanian Bioethics Committee (No. BEC-MG-173); the permission to collect medical records from the hospital was obtained as well.

The study used birth registry records that included basic information such every bit age, previous pregnancies and deliveries, and clinical diagnoses. Women with mental disorders were selected based on the International Classification of Diseases Codes (ICD-10), and medical records were retrieved from the medical archive.

The diagnoses of mental disorders (according to the ICD-10) in the study group were as follows: schizophrenia; schizotypical and delusional disorders (F20–F29); mood (melancholia) disorders (F30 − F39); neurotic stress related and somatoform disorders (F40–F48); mild mental retardation (F70); behavioral disorders due to utilize of psychoactive substances (F10 − F19); and other (Table i). Information technology was establish that 32.1% (n = 41) of the women in the study group were using psychotropic medication during their pregnancy, namely antipsychotics (n = xvi, 12.two%), antidepressants (n = 05, iii.eight%), benzodiazepines (due north = 07, 5.38%), and psychotropic polytherapy (n = 13, 9.ix%). The majority of women who had the diagnosis of behavioral disorder due to the use of psychoactive substances used heroin or amphetamines (n = 11, 91.half-dozen%).

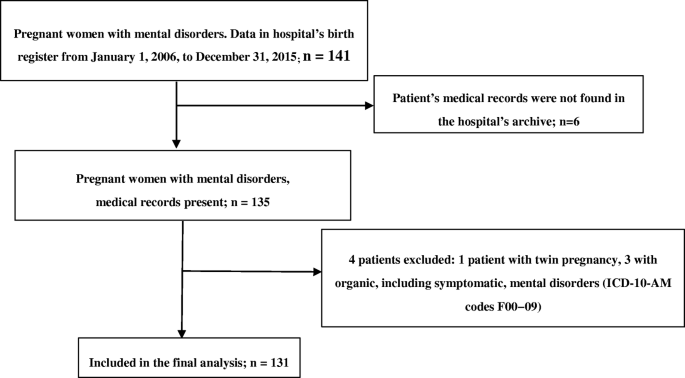

The total number of women who gave birth at the infirmary during the period of January 1, 2006, to December 31, 2015, was 34,638. The final study grouping was comprised of 131 pregnant women with mental disorders. Patients with organic including symptomatic, mental disorders (ICD-0-AM codes F00 − 09) and twin pregnancies were excluded (Fig. i).

Flowchart of study participants, according to the hospital's nativity registry information

Each participant from the study group was matched with ii mentally healthy controls with unmarried pregnancies, who were matched past historic period, year of commitment, and number of previous pregnancies and deliveries. A total of 262 command women were selected, only the last control group consisted of 228 pregnant women as the medical records of 34 women were missing from the hospital's archive.

Data regarding women'due south sociodemographic status, concomitant diseases, pregnancy complications and course, process of delivery and available information on newborns were used in the analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed with the IBM SPSS Statistics v21 program using contained samples, Kolmogorov–Smirnov, chi-square and Mann − Whitney tests. Multiple logistic regression models were constructed to decide the upshot of mental disorders on diverse dependent variables. The degree of error was prepare below 5% as the threshold of statistical significance (p < 0.05).

Results

Of the 403 medical records of meaning women, 359 fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The mean maternal age at delivery did not differ significantly between the study group and good for you controls (xxx ± six.4 vs. 30 ± five.nine years). The number of previous deliveries and pregnancies also did not differ significantly (Table 2).

Women with mental disorders were more likely to have chief education (31.2% vs. 8.0%; p < 0.001), to be unmarried (54.2% vs. 25.4%, p < 0.001), to accept lower working capacity (33.eight% had lower working capacity considering of their mental illness), and less likely to be employed (31% vs. 73.6%; p < 0.001) than their healthy counterparts. In addition, women with mental disorders more oftentimes had concomitant somatic diseases (69.nine% vs. 36.6%; p < 0.001) and smoked during pregnancy (34.1% vs. eight.4%; p < 0.001) (Table 2).

The women of the study group more often did not seek ANC (19% vs. i.three%; p < 0.05), had fewer ANC visits (vi ± iv.i vs. 8 ± 3.1; p < 0.05) (the mean number of ANC visits for multiparas and primiparas approved past the Lithuanian Ministry building of Health is seven and 10, respectively), and had college rates of hospital admissions during pregnancy (55.7% vs. 30.3%; p < 0.001). However, the incidence rate of UTIs, pyelonephritis, hypertension, hypertension with eclampsia and gestational diabetes mellitus did not differ between the groups (Table 2).

There was no divergence in the methods of delivery. Moreover, mentally sick women and healthy controls did non differ significantly regarding the rates of vaginal commitment, constituent and emergency CSs, and epidural analgesia. Women with mental disorders spent significantly more than days in the hospital in the postpartum period (p < 0.05): the boilerplate was 6 days subsequently elective CS, 8 days after emergency CS, and v subsequently vaginal delivery compared with the control group with the corresponding averages of 5, 7, and 4 days.

The newborns of the mentally ill women were pocket-sized for gestational age more often (12.9% vs. seven.6%; p < 0.05). Other adverse outcomes such as prematurity, stillbirths, major malformations, depression birth weight, and the Apgar scores lower than 7 after 5 min were more common in the report grouping, simply without significant difference. The women with mental disorders were less likely to breastfeed their newborns (71.iii% vs. 94.three%; p < 0.001) (Table 3).

After adjusting the model of logistic regression, the data revealed mental disorders to be a significant predictor of lower education, unemployment, being unmarried, having chronic concomitant diseases, smoking, hospitalization during pregnancy, weight proceeds of < 10 kg, and lower ANC attendance. Equally regards neonatal outcomes, mental disorders were a predictor of having an SGA newborn and the choice to not breastfeed (Table four).

To avoid possible bias and the impact of concomitant diseases every bit well as psychotropic medication used, adjusted statistical assay was performed. The results remained the aforementioned with some slight differences (Table 5).

5 (3.8%) women from the study group were transferred to the psychiatric section postpartum due to exacerbation of mental disorder. One adult female had a behavioral disorder due to the utilise of psychoactive substances (heroin); other had a diagnosis of schizophrenia and experienced a psychotic episode after delivery. The remaining three women were originally hospitalized to the psychiatric section, and after delivery, they were transferred back due to a lack of progress in the handling of their mental disorder (hebephrenic schizophrenia, reoccurring depressive disorder, and bipolar affective disorder).

Discussion

The morbidity rates due to mental disorders are high in Lithuania, and in 2014 they were 2.5 times college than the European average [13]. However, this report, analyzing pregnancy and neonatal outcomes of women with pre-existing mental disorders, was the commencement to be conducted in Republic of lithuania.

Our data suggest that significant women with mental disorders were more than probable to have lower social status and were more susceptible to tobacco employ during pregnancy. The relative risk of low education and unemployment was 4 and 6 times higher, respectively, in women with mental disorders than good for you controls. The reason behind such behavior remains unclear as it is very hard to determine whether it is due to the mental illness itself or a social shift associated with it. These women did not receive adequate ANC during their pregnancy as the study grouping had low ANC attendance rates and engaged in dangerous activities, such as usage of psychoactive substances and smoking. Multiple studies accept reported the correlation betwixt the mental health of a meaning woman and risky behavior during pregnancy, for example lower ANC attendance [14, 15]. In our written report, in that location were more smokers among women with mental disorders than good for you controls (34.1% vs. 8.4%), and women with mental disorders were more likely to be engaged in risky behaviors during pregnancy. Women in the study group were at a four-fold and a 2-fold greater adventure of smoking and attending fewer ANC visits, respectively, than their healthy counterparts.

Maternal smoking is significantly associated with smaller birth weight and length, as well as it causes poor birth outcomes [xvi,17,18]. The college rates of prematurity, stillbirths, major malformations, lower Apgar scores and newborns with low birth weight (LBW) were observed more than often in the written report grouping, simply the difference was non meaning, virtually probably because the sample size was not big enough. However, the results suggest a possible clan between mental disorders and a negative impact on newborn health. The same clan was noticed in other studies [nineteen,20,21,22]. Although we did not find any significant difference in the rate of delivering premature newborns, there are contradictory findings on whether mental disorders and being exposed to psychotropic medication are take chances factors for having a premature newborn [ix, 23].

We found a significant difference in the rates of delivering SGA newborns between the groups: a pre-existing mental disorder doubles the risk of giving birth to an SGA newborn. These findings are consistent with other studies on the effects of mental disorders on pregnancy [24, 25].

Women with pre-existing mental disorders had a longer postpartum recovery fourth dimension in hospital. According to the official statistical data, an average infirmary stay in the psychiatric and obstetric departments of Kaunas Klinikos is 13.5 and 4.07 days, respectively [26]. There were women transferred from the psychiatric section to the obstetric department considering they were in labor and then after giving birth transferred dorsum to the psychiatric department to continue their treatment. Some were transferred to the psychiatric department subsequently giving birth for handling because they had relapsed. Women from the study group who were transferred to or from the psychiatric department had an increased average length of hospital stay upwardly to 32 days.

The study was conducted in the University Hospital of tertiary care, which is the largest healthcare institution in Lithuania. The University Infirmary has been recognized as a Baby Friendly Infirmary considering of how information technology protects, promotes, and supports breastfeeding, and for its facilities providing maternity and newborn services. Nevertheless, women with pre-existing mental disorders were less likely to breastfeed their newborns: the relative adventure of non breastfeeding increased by about vii times.

There was no significant deviation in the method of delivery between the study grouping and healthy controls. Both elective and emergency Caesarean sections (CSs) were performed in 20.half-dozen% and 23.ii% of the women from the study and control groups, respectively. Still, a matched, controlled cohort study past Howard et al. [xv] reported a significant difference between the groups (twenty% vs. 14%) with the study group requiring CSs more frequently. This tin be explained, still, by differences in methodology and past the dissimilar clinical practices used in different countries and hospitals. Our written report was performed in a highly specialized, 3rd infirmary with a considerable number of high-hazard deliveries, while the previously mentioned written report used records from a General Practice Inquiry database [15]. The results of some other study, which was performed in ii tertiary obstetric hospitals, are closer to those found by the states, with 20.ii% of women with mental disorders requiring constituent and xvi.i% having emergency CSs [27].

Limitations

Because of the infrastructure of the wellness organization and data protection restrictions in Republic of lithuania, it was not possible to admission patient records from the participants' primary care physicians or data from their psychiatrists. Only information available during delivery, in nascence registry records, was used for the identification of cases; therefore, a pregnant number of pregnant women with balmy mental disorders may have gone unmentioned during nascence and therefore been missed. There may be some inaccuracies in the medical records regarding whether patients were receiving psychotropic medication at the time of their pregnancy. The stigma of mental affliction must also exist taken into account, since some of the patients from the command group may have concealed that they as well had a mental disorder. The motivation for doing so is reinforced past fearfulness of custody loss afterward becoming a parent [28].

Since the study was performed in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Lithuanian University of Health Sciences Kauno Klinikos – a highly specialized hospital – it may not stand for the most common problems that medical professionals face in their daily work, with regards to pregnant women with mental disorders. For case, pregnant women from the control group may have had higher incidence rates of concomitant diseases than women who give nascence in less specialized hospitals, and this could accept contradistinct the results of this written report.

Further research in this field is essential, and a prospective design would be more informative. A prospective written report would enable researchers to perform more homogenic and objective assay of patients with mental disorders, to access more than data on their psychotropic drug apply during pregnancy, and to access data concerning long-term outcomes for both newborns and mothers.

Conclusions

To conclude, pregnant women with mental disorders were more probable to be less educated, unemployed, unmarried, smokers and to accept concomitant diseases. Moreover, they did not know the date of their last menstrual period, did non seek ANC more often, had fewer omnipresence visits, gained less than 10 kg of weight per pregnancy, and had more hospital admissions. As compared with good for you controls, mentally ill pregnant women delivered small-for-gestational-historic period newborns significantly more oft and were less likely to breastfeed. Other neonatal outcomes tended to be worse, merely the difference was not significant. No difference in the incidence of pregnancy-related diseases or the delivery methods chosen was institute when comparing the groups.

Availability of data and materials

Equally the information were acquired in Lithuanian, the data sets analyzed for this report will be made available from the corresponding author G. S. upon reasonable asking.

Abbreviations

- SGA:

-

Small-scale for gestational age

- ICD – 10:

-

International classification of diseases – 10

- UTI:

-

Urinary tract infection

- CS:

-

Caesarean section

- LMP:

-

Last menstrual menstruum

- ANC:

-

Antenatal care

- GDM:

-

Gestational diabetes mellitus

- LBW:

-

Low birth weight

References

-

Earth Health Organization. Mental Health Determinants and Populations Section of Mental Health and Substance Dependence. Maternal and child mental wellness program. 2016. http://www.who.int/mental_health/maternal-child/maternal_mental_health/en/.

-

Cannon Thousand, Jones PB, Murray RM. Obstetric complications and schizophrenia: historical and meta-analytic review. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(vii):1080-92.

-

Hoirisch-Clapauch South, Brenner B, Nardi AE. Adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes in women with mental disorders. Thromb Res. 2015;135(ane):60 – 3.

-

Judd F, Komiti A, Sheehan P, Newman L, Castle D, Everall I. Adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes in women with severe mental illness: To what extent can they be prevented? Schizophr Res. 2014;157(1–3):305–9.

-

Maghsoudlou S, Cnattingius Southward, Montgomery S, Aarabi M, Semnani S, Anna-Karin Wikström. et al. Opium utilise during pregnancy and infant size at birth: a cohort study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2018;18(1)358.

-

Kalaitzopoulos D, Chatzistergiou Thousand, Amylidi A, Kokkinidis D, Goulis D. Effect of Methamphetamine Hydrochloride on Pregnancy Consequence. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2018;12(iii):220–6.

-

Nguyen TN, Faulkner D, Frayne JS, Allen Southward, Hauck YL, Rock D, Rampono J. 2012.Obstetric and neonatal outcomes of meaning women with astringent mental illness ata specialist antenatal clinic.2013; 199(3): 26–ix.

-

Sadowski A, Todorow M, Yazdani Brojeni P, Koren G, Nulman I. Pregnancy outcomes post-obit maternal exposure to 2nd-generation antipsychotics given with other psychotropic drugs: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(7):e003062.

-

La Merrill M, Stein CR, Landrigan P, Engel SM, Savitz DA. Prepregnancy trunk mass index, smoking during pregnancy, and babe nativity weight. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21(vi): 413 – 20.

-

Chang H, Keyes K, Lee K, Choi I, Kim S, Kim K. et al. Prenatal maternal depression is associated with low birth weight through shorter gestational age in term infants in Korea. Early Human Dev. 2014;90(1):15–20.

-

Ehrenkranz R. Neonatal Outcomes After Prenatal Exposure to Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Antidepressants and Maternal Depression Using Population-Based Linked Health Data. Yearbook of Neonatal Perinatal Medicine. 2007;2007:34–viii.

-

Shah P. Paternal factors and low birthweight, preterm, and pocket-sized for gestational age births: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(two):103–23.

-

Našlėnė Ž, Ustinavičienė R, Želvienė A. Health of Lithuania's residents in the context of European Wedlock. The Found of Hygiene. Health Information Middle. 2016;one–79; http://www.hi.lt/uploads/pdf/leidiniai/Informaciniai/Lietuva%20ES%20kontekste.pdf. Accessed 23 Jul 2017.

-

Ferraro AA, Rohde LA, Polanczyk GV, Argeu A, Miguel EC, Grisi SJFE, Fleitlich-Bilyk B. The specific and combined part of domestic violence and mental health disorders during pregnancy on new-born health. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:257.

-

Howard L, Goss C, Leese Grand, Thornicroft G. Medical outcome of pregnancy in women with psychotic disorders and their infants in the outset twelvemonth after birth. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182(01):63–7.

-

Abraham Chiliad, Alramadhan Southward, Iniguez C. et al. A systematic review of maternal smoking during pregnancy and fetal measurements with meta-analysis. PLoS Ane. 2017;12(ii):e0170946.

-

Peterson LA, Hecht SS. Tobacco, e-cigarettes, and kid health. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2017;29(2):225–30.

-

Inoue S, Naruse H, Yorifuji T. et al. Touch on of maternal and paternal smoking on nascency outcomes. J Public Health (Oxf). 2017;39(three):ane–10.

-

Staneva A, Bogossian F, Pritchard G, Wittkowski A. The effects of maternal depression, anxiety, and perceived stress during pregnancy on preterm birth: A systematic review. Women Birth. 2015;28(iii):179–93.

-

Tomita A, Labys C, Burns J. Depressive Symptoms Prior to Pregnancy and Infant Depression Birth Weight in S Africa. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(ten):2179–86.

-

Zhao L, McCauley Thou, Sheeran L. The interaction of pregnancy, substance apply and mental affliction on birthing outcomes in Commonwealth of australia. Midwifery. 2017;54:81–eight.

-

Boyle B, Garne East, Loane M, Addor Chiliad, Arriola 50, Cavero-Carbonell C. et al. The irresolute epidemiology of Ebstein's anomaly and its human relationship with maternal mental wellness weather: a European registry-based study. Cardiol Young. 2016;27(4):677–85.

-

Sutter-Dallay A, Bales M, Pambrun E, Glangeaud-Freudenthal Northward, Wisner G, Verdoux H. Bear upon of Prenatal Exposure to Psychotropic Drugs on Neonatal Upshot in Infants of Mothers With Serious Psychiatric Illnesses. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2015;76(07):967–73.

-

Vigod S, Kurdyak P, Dennis C, Gruneir A, Newman A, Seeman Grand. et al. Maternal and Newborn Outcomes Amongst Women With Schizophrenia. Obstetric Anesthesia Digest. 2015;35(ii):100.

-

Smith M, Shao L, Howell H, Lin H, Yonkers K. Perinatal Depression and Birth Outcomes in a Healthy Commencement Project. Matern Child Health J. 2010;15(iii):401–nine.

-

Hospital Beds Utilization in 1998–2018 (data of annual reports). [Cyberspace] 2016. https://stat.hello.lt/default.aspx?report_id=252 (24 07 2018).

-

Galbally Thou, Frayne J, Watson S, Snellen M. Psychopharmacological prescribing practices in pregnancy for women with severe mental illness: A multicentre written report. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018. https://doi.org/x.1016/j.euroneuro.2018.11.1103.

-

Dolman C, Jones I, Howard LH. Pre-conception to parenting: a systematic review and meta-synthesis of the qualitative literature on motherhood for women with astringent mental disease. ArchWomens Health. 2013;16(three):173 – 96.

Acknowledgements

The manuscript was edited past Jurgita Grigienė Jurgita.Grigiene@lsmuni.lt.

Funding

This enquiry received no external funding.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have read and canonical the manuscript. GM, KS and KJ : methodology, formal analysis, investigation, resources, writing—original typhoon training, visualization, data curation; IN and GM: formal assay; KJ, AJ, MM and VA: writing—review and editing, supervision.

Respective author

Ethics declarations

Ideals approval and consent to participate

The written report was canonical by the Bioethics Centre, Lithuanian University of Wellness Sciences (No. BEC-MG-173).

Consent for publication

Not applicative.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they take no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits employ, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, equally long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and betoken if changes were made. The images or other third political party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article'due south Creative Commons licence and your intended apply is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission straight from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Artistic Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made bachelor in this commodity, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and Permissions

About this commodity

Cite this commodity

Sūdžiūtė, K., Murauskienė, G., Jarienė, K. et al. Pre-existing mental health disorders affect pregnancy and neonatal outcomes: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 20, 419 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03094-5

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1186/s12884-020-03094-5

Keywords

- pregnancy

- mental disorders

- antenatal care

- commitment outcomes

- neonatal outcomes

Source: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-020-03094-5

0 Response to "Can a Woman With Mental Illness Have a Baby"

Post a Comment